In Praise of Paywalls

Or; How I learned to stop skimping and pay for the New Yorker

It’s almost been three months since the New Yorker opened its delectable digital pantry to all comers. Billed as a “summer-long-free-for-all”(despite arriving rather haphazardly at the season’s end), the door to a decade’s worth of literary treats was left ajar, a lure in anticipation of the imminent paywall and monthly reading quotas.

I had a plan for these precious twelve weeks. I would use and abuse the privilege of unlimited access – searching and saving articles, essays, fiction and poetry left and right, amassing a treasure trove of material to last me until they were foolish enough to let their guard down again. I may have cackled with self-satisfied delight.

Yet now, as the final days run down, I’m having some difficulty leaving the scene with my ill-gotten goods. I would hardly have considered shelling out for this old dame of American letters in the heady days of July, but now, having spent so many intervening hours devouring articles and essays, sampling short stories and nibbling on witty riposts, I am possessed by the staunch recognition that damn, there’s a lot of great writing going on in here.

Something has changed in my relationship to consumption at the great online buffet. It’s not just that I have become resigned to paying that dollar a week for the New Yorker once the paywall is up – I want to.

It’s not the first time. A few weeks ago I reached the end of the first volume of the app-based novel The Silent History. The discovery that I had to put down another ten for access for the next installments didn’t illicit the ire it would have a year or two ago – I just clicked on through. For months I’ve subscribed to the pay-what-you-want digital comic The Private Eye by Brian K. Vaughn and Marcos Martin, and long ago stopped assiduously weighing my lowest price vs guilt threshold. Rather, I'll opt for the recommended price and click on through. It has begun to feel… normal.

Paying for what we read online – who would have guessed? This is a cultural shift years in the making, the latest unsteady lurch in the ongoing renegotiation of our relationship to media in the internet age. And it may be yet another harbinger of the end of the anarchic, wild west internet as we knew it, tamed by government muscle and corporate cash (though still no shortage of dirty saloons).

The music industry, pulled from the physical realm kicking and screaming, found a means of monetizing digital delivery years ago, stemming its (largely self-induced) haemorrhage. File sharing has hardly vanished, but the myriad of legal alternatives, from the iTunes store to Spotify, have made it less convenient, less rewarding and, perhaps most essentially, less habitual.

Words have remained on the frontier. Years, even decades, of habit have taught us to expect writing to be free for our perusal online. Novels may have got a pass (who read novels on their computer screen pre-ereader anyway?), but day-to-day content – our morning news, distractions at work, research, entertainment – has always been readily available. Why pay when no one is asking? Why even consider it when there are millions of online town criers easily satiated by recognition, clicks and comments? We could read on, untroubled, as industries flared and burnt.

Yet the calculus for why they should charge, and why we should pay, is pretty damn simple. Good writing is costly, print sales are in decline, and online advertising cannot cover the cost chasm. The benevolence of profit-hungry corporations and the promises of government culture funding are hardly reliable stopgaps.

Newspapers have been the most prolific casualties. The solution was always simple – to charge, as they had with the print editions churned out for over a century – but many have opted rather for what Molly Ivins declared “a slow suicide.” Publishers saw the web as an unnecessary adjunct to their main line of business – only to find their sales eroded not only by the armada of bloggers and online upstarts, but by their own industry giving it away for free in pursuit of an “online presence”.

Ebbing revenues have sent newspapers in a predictable and repetitive spiral: management underpays, closes offices and fires staff to maximise short-term profits, hobbling the work itself and thereby hampering future sales; they repeat until corporate owners order the business cannibalised or sold limb-by-butchered-limb. Sometimes advertisers have their way with the emaciated body first, hands wrapped around the chin to make the mouth tell whatever sweet lies they desire – it is rarely a dignified demise

Paywalls may not a solution to all of an industry’s ills, but they do work. Leading the charge has been the New York Times, which first instituted its metered model in 2011. Reaction was initially hostile to this attack on the wisdom of unfettered access, but the reason every second paper has opted to cling to the Grey Lady’s hem is all in the numbers – today there are over 800,000 digital-only subscribers (outnumbering print), and, rarer still, revenues are up.

Although alternative models are rife, all-too-often they’re niche solutions, based on deep pockets or finely honed demographics. The Guardian, ever the contrarian, has had great success expanding its international market share with a “no paywall, ever” model, even labelling its editorial columns “Comment is Free” as socially conscious riposte. However, its confidence is hard to emulate, given the paper is supported not by shareholders but by an enormous, billion-dollar trust to be drawn from in perpetuity.

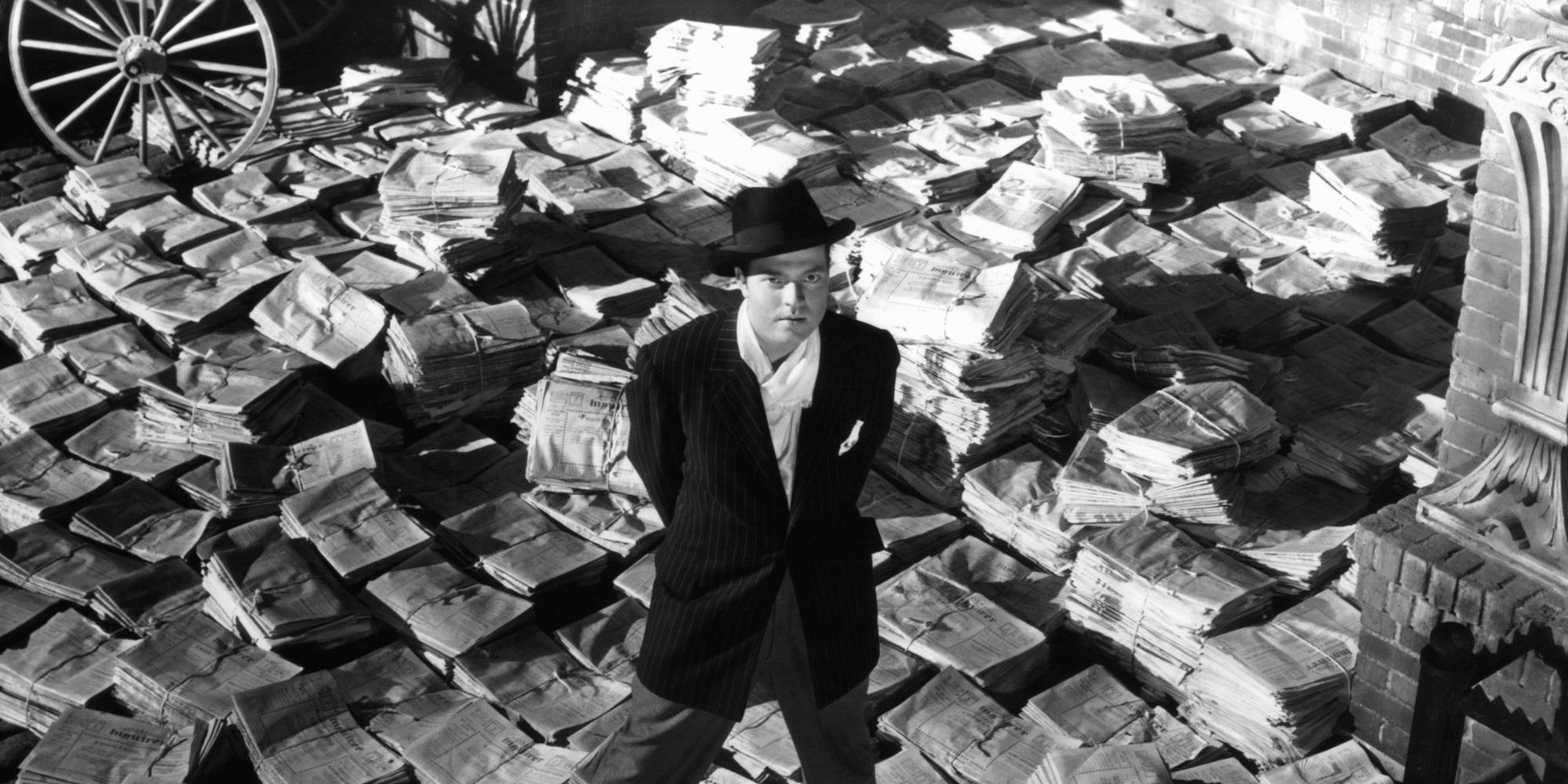

The same goes for ideological nemesis, News Corp, whose newspaper business has been buoyed by Rupert Murdoch’s willingness to take the hits of negative profitability in his pursuit of market supremacy. One is reminded of the young Orson Welles as newspaper magnate Charles Foster Kane rejoining, with a twinkle in his eyes:

“You're right, I did lose a million dollars last year. I expect to lose a million dollars this year. I expect to lose a million dollars *next* year. You know, Mr. Thatcher, at the rate of a million dollars a year, I'll have to close this place in... 60 years.”

Less successful have been those online entities that refuse to erect an outright paywall, but instead ask readers to spring for ‘extras’. The once-mighty Slate (where one could get frequent doses of Christopher Hitchens and Anne Applebaum), otherwise compromised by sponsored articles and integrated advertising, spruiks its ‘Slate Plus’ subscription, inviting users to sign up for a free mug, “special access to your favourite writers and editors”, “30% off live events” and “20% off merchandise.”

Similar to mobile games that are offered as a free download but attempt to juice revenue by selling character skins, bails of hay or weaponry in-app, I feel this model fundamentally cheapens the product and its audience. It assumes that readers will pay only for frivolities and minutia, whilst attaching no similar value to the core product – the damn writing. If a paywall reflects an unerring confidence that readers will pay for the work if asked, ‘Premium’ subscriptions resembled pan-handling aimed at the most devoted (and, presumably, deep-pocketed) of readers.

In a crisis of capital, many papers have jumped with reckless abandon into the arms of journalism’s old uneasy bedfellows – advertisers. Recognising at last the futility of banners and pop-ups, we’re now plagued by the more insidious ‘advertorials’. I couldn’t express the suspicion and loathing this sell-off deserves any better than John Oliver, so I’ll just leave him here:

Unsurprisingly, the websites that have most expertly exploited ‘free access’ as a business model have been those that were suckled at infancy on the digital breast. Many, like Gawker or Buzzfeed, thrive on click-bait. Budding news empire VICE has grown rapidly by adroitly tailoring its content towards prominently-featured sponsors, embracing high profile stunts (Denis Rodman in North Korea!) and partnerships (a weekly series on HBO).

These websites certainly have their place – but they are rarely a breeding ground for thorough investigative journalism or considered writing. The thirst for clicks and click-throughs privileges rapid consumption rather than immersion, dancing on the ruins of the old journalism but building very little in its place. VICE may rightly boast some exceptional international exposés– but they are unlikely to ever staff an office of correspondents in Africa or Asia to replace those shuttered by the ailing papers of yesteryear. Buzzfeed prospers not by aspiring to rest at the centre of anyone’s news and entertainment universe, but by exploiting our divided attentions when staring at the ever-more-cluttered sky.

But paying for writing isn’t just about protecting the bottom line of adaptation-challenged industries. It’s also about reader ownership. The internet has given us a greater capacity to interact with and shape the work we consume: the barricade between creator and consumer has been whittled away by blogs, Twitter and long comment tails. That sea change promises a relationship with writing that is not just as habitual as the old morning paper, but personal. It’s a loyalty that we've shown to be willing, through subscriptions, donations and pay-what-you-will systems, to express in dollars and cents as well as eyeballs.

That more direct ownership may even be able to redress a very old power imbalance in media. If interference by advertisers is a blight on journalism today, it is only the latest manifestation of a tension that has long limited what we read and watch. Digital subscriptions however, by expanding the pool of potential readers (free of the limits once placed by production and delivery costs) can cut back the insidious reliance on shysters and marketers. The New York Times now has 56% of its revenue coming directly from readers, a historical high. Publications will inevitably cater to whoever is paying the bills – surely it is better for our souls and sanity if that’s us, and not a cadre of advertisers?

I’ve also found the sense of ownership (and the price tag) can force a worthwhile re-examination of one’s own reading habits. The breadth of articles and general quality of reporting from the International New York Times (in spite of bouts of editorial chaos and rogue writers in the culture department) sold me on dropping double digits monthly. Conversely, the belated institution of a paywall for my long-standing local, The Sydney Morning Herald, divorced from the years of home-delivered broadsheets, forced me to confront the paper’s sad cycle of decline, and turn instead to the embrace of the burgeoning Australian off-shoot of The Guardian.

In that sense, a paywall is a gamble - putting the onus once more on the work itself, rather than simple convenience. But that’s the way it should be. Price points might kill yet more newspapers and magazines, but for those that survive we will have ensured a future not just for talented amateurs online, but professionals – journalists, writers and artists trained in their craft, not simply co-opted for enthusiasm's sake. Reluctant as we may be to reduce yet more of the online space to a commodity, and to throw up further gated communities, we do writing no favours by separating it from the bevy of purchasing decisions we already tacitly accept when it comes to film and music.

Publishers have taken a long time – too long perhaps – to confront the issues inherent with writing in the digital age. Now, having finally decided to embrace the value of their work, the rest is up to us. Sure, it's a different deal than the one we signed up to in the wild early days on the frontier, when everything was free for the taking, nailed down or no – but if we pine for an online landscape with space for more than advertorials and ephemera, we’re best to accept it.

So when the wall goes up at the New Yorker in a few days, I’m resigned – I’m buying. It can slot beside The New Yorks Times for my news, The Monthly for my local commentary, Overland and Seizure for my smattering of essay and prose. Those next 6 volumes of The Silent History? Already ordered. The Private Eye? Following to the end.

A paywall is its own promise - of integrity, of less click-baiting and a repudiation of hit-whoring. It signals a publication that has a debt to readers before advertisers. The model isn’t quite there – but has lurched close enough that I can believe in a future for quality writing in the decades to come. And that’s a decent start.

But while the walls are still down – have at it. Here are a few of my favourites discovered in the New Yorker’s fast-shutting pantry:

The Last Amazon - On the feminist origins and revival of Wonder Woman

Master of Play - On Shigeru Miyamoto, Nintendo creative kingpin and father of Mario, Donkey Kong and Zelda

The Fight of Their Lives - On the Kurds in Iraq striving for independence and leading the fight against ISIS

Utopian For Beginners - On the creation of a new, perfect language

The Masked Avengers - On Anonymous and the rise of online vigilantism

Danse Macabre - On turmoil at the legendary Bolshoi Ballet - acid-attack included

Netherland - On the slow-acting tragedy of youth homelessness in New York